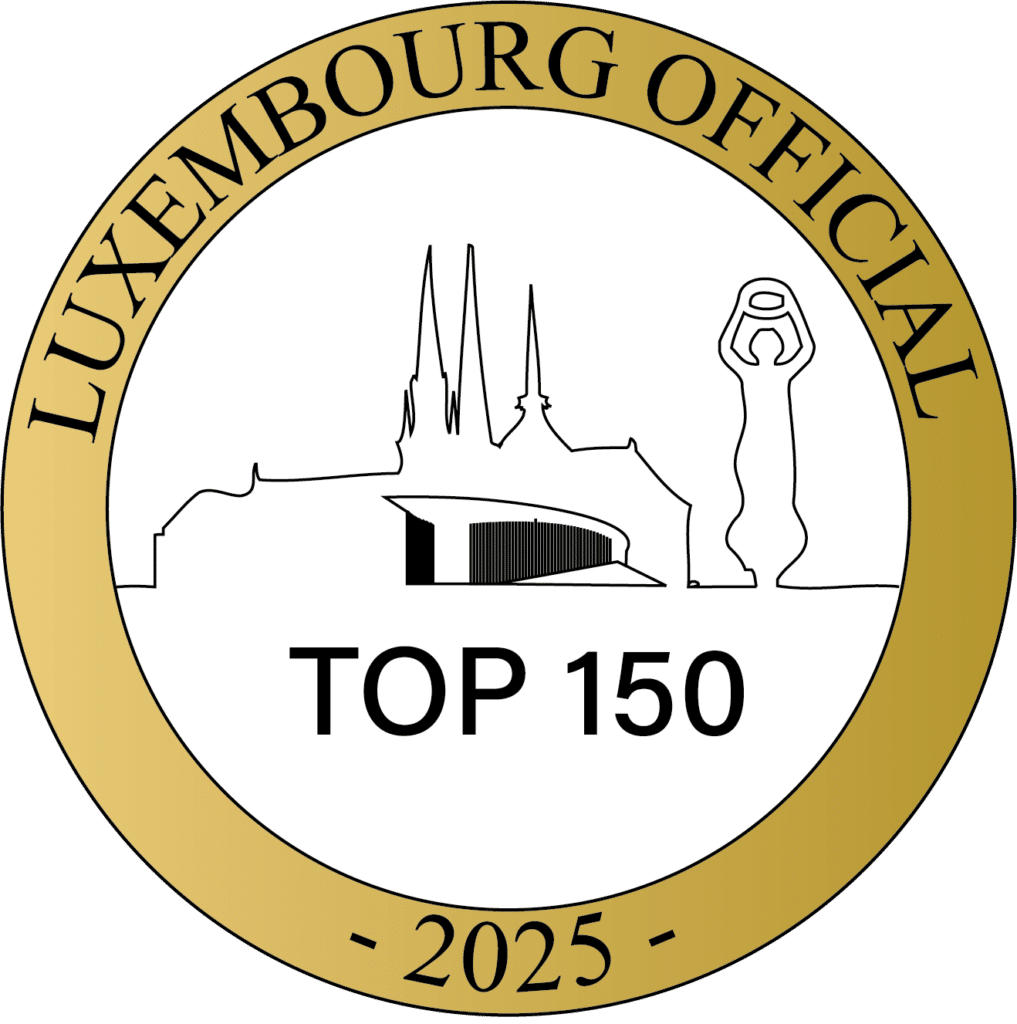

Keynesian economics is a macroeconomic framework founded by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s. It emphasises active government involvement to manage aggregate demand, stabilise economic cycles, and support employment during downturns.

John Maynard Keynes: How Keynes Reshaped Economic Policy

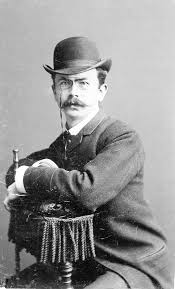

John Maynard Keynes, born in Cambridge in 1883, was a British economist whose work redefined modern macroeconomic theory. Educated at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, he began his career in the India Office before serving in the British Treasury during World War I. He rose to prominence after publishing The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), in which he criticised the reparations imposed on Germany. Throughout his life, John Maynard Keynes combined academic analysis with government service, laying the foundations for policies designed to manage economic cycles and maintain employment.

Principles of Keynesian Thought

Keynesian economics views aggregate demand—consisting of consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports—as the primary determinant of overall economic activity rather than supply. It posits that prices and wages adjust slowly, creating rigidities that prevent markets from clearing quickly during downturns. This sluggish adjustment means unemployment and underutilised capacity may persist when demand is insufficient. Keynesianism characterises the economy as inherently unstable; spending shocks can trigger prolonged recessions unless countered by policy interventions. The consumption function links income to spending behaviour, the marginal propensity to consume influences multiplier outcomes, and liquidity preference describes how interest rates determine money demand. These core ideas collectively challenge the assumption that economies naturally recover to full employment.

Policy Instruments and Mechanisms

Under Keynesian doctrine, fiscal policy plays a central role in addressing demand shortfalls. Governments should increase public expenditure or cut taxes during recessions to offset the decline in private sector demand. The Keynesian multiplier effect amplifies the impact of such stimulus: when households receive additional income, they spend a portion, thereby generating further income and consumption throughout the economy. Monetary policy complements fiscal actions by maintaining low interest rates to encourage borrowing and investment, reducing the attractiveness of holding cash. Coordination between fiscal and monetary authorities is essential to ensure demand is supported when private activity falters. Keynesian policy frameworks also emphasise timing and scale—interventions must be swift and sufficient to close output gaps.

“The political problem of mankind is to combine three things: economic efficiency, social justice and individual liberty”

Evolution and Critiques

From the mid-20th century, Keynesian models evolved with formal constructs like the IS‑LM framework, offering mathematical representations of interest rate–output relationships under different market conditions, incorporating wage and price rigidities. Later adaptations, known as New Keynesian economics, introduced concepts such as rational expectations and price stickiness due to menu costs, addressing earlier criticisms while preserving the role of active policy. Keynesianism gained widespread influence in post-war economic planning but faced challenges during the 1970s stagflation period, when high inflation combined with stagnant growth. Monetarists argued that excess government spending caused inflation without reducing unemployment, while Austrian economists asserted that intervention distorts price signals, leading to misallocation of resources and economic inefficiencies.